The following is a job talk I delivered a few years back. I leave in obscurity where exactly it was given. Let’s just say that the follow-up questions predictably featured accusations of “Hegelianizing” Christology, though at least one prominent accuser seemed unaware of the relevant historical texts and conciliar tradition, or that Hegel did not, after all, coin the term “synthesis,” which is a perfectly good Greek term cherished by all of the above.

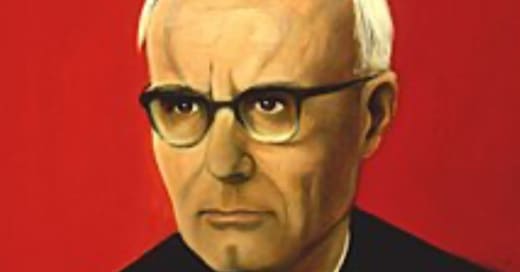

In an Easter homily entitled, “Christ the Liberator,” then Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger quotes a passage from one of Epiphanius’s own Easter homilies wherein Christ speaks these words to Adam: “I am your God, yet I have become your son. I am in you, and you are in me. We together are a single, indivisible person.”1 It is clear, Ratzinger comments, “that this Adam does not signify an individual in a dim and distant past: the Adam addressed by the victorious Christ is we ourselves…. This pronouncement contains the whole Christian message of Easter.”2

Christology raises the most fundamental questions about God’s relation to us, questions of identity and difference, of persons and natures, of our beginning and end in the God-human, Jesus Christ. Today I’d like to commend so-called “Neo-Chalcedonian Christology” as eminently worthy of retrieval, a crucial aid in reflecting systematically on the main themes of Christology. My tasks are two: I need first to summarize the rise or return of Neo-Chalcedonianism in historical scholarship of the last century and then to distill something of Neo-Chalcedonianism’s systematic promise for Christology today.

I. Historical Return

A. “Neo-Chalcedonianism.” Neo-Chalcedonianism was coined in 1909 by the eminent Syriac patrologist, Joseph Lebon. He used it to describe the opponents of Severus of Antioch, the most strident and influential anti-Chalcedonian theologian of the sixth century. Neo-Chalcedonians, Lebon said, bore two basic characteristics. First, they renewed efforts to interpret Chalcedon through Cyril of Alexandria’s more unitive, “single-subject” Christological focus (hence “Neo-”). Second, they did so by wielding a highly technical “scholastic” apparatus in view of developing Chalcedon’s talk of natures/essences and hypostases/persons. Scholars later appended a more precise criterion: Neo-Chalcedonians practiced a sort of “dialectical” method that affirms simultaneously Chalcedon’s symmetrical dualities (two births, two consubstantialities, two natures) and Cyril’s formulations of identity, even the much controverted “one-nature” formula (“one nature of the Word incarnate”).3 The great task of Neo-Chalcedonian Christology, then, was to burnish Chalcedon’s “Christo-logic” as a logic that compels us to reconceive what it means to be “one” hypostasis/person and “two” natures/essences in a single, concrete life—that of Jesus Christ.

B. “Christo-logic.” Patrologists and historical theologians are still very much in the process of detailing the many twists and turns in Neo-Chalcedonianism’s emergence. That drama features many major and minor players, each worthy of further study: John the Grammarian, Leontius of Byzantium, Leontius of Jerusalem, Pamphilus of Caesarea, Theodore of Raithu, the Emperor Justinian and the Second Council of Constantinople, Anastasius of Sinai, and (of course) Maximus the Confessor.4 But instead of chasing that narrative, let’s take a more schematic view of Neo-Chalcedonian Christology, particularly as perfected (in my view) by the likes of Leontius of Byzantium and especially Maximus the Confessor. Our schema consists of two main developments: [1] the distinction of the logic of nature vs. the logic of person; [2] the reintegration of both logics into a single logic of the person as—to use Constantinople II’s new term—the “synthesis” of naturally differing realities.

1. Logics of nature vs. person. Chalcedon declared but did not explain that what is “one” in Christ is his hypostasis/person and what is “two” are his natures/essences. The first thing to notice is that nature and person must therefore differ. Of course, these terms had long histories stretching back through philosophical and patristic traditions alike. The Cappadocian Fathers, in particular, made the distinction a key component in their pro-Nicene trinitarian theology (though not always harmoniously in the details). For them person relates to nature as particular to universal.5 But, as Johannes Zachhuber has shown extensively, this view of the distinction did not suffice for the unique problems raised in Chalcedon’s aftermath. Severus of Antioch pressed the issue by asking: Was Christ’s human nature universal or particular? If universal, then Christ would be incarnate in the entire human race (since the universal, if real, is really in all particulars). If particular and thus concrete, then Christ’s humanity would seem to present us with another hypostasis/person. The latter leads to Nestorianism, the former to something bizarre enough that few wished to defend it (although Maximus did in his own way).

Neo-Chalcedonians had to articulate “person” in such a way that it alone is what’s positively and really “one” in Christ, but not one in the way that universals or particulars as such are one. In other words, person had to be real in a way that exceeded the very universal-particular dialectic. Hence Leontius of Byzantium proposed an apparently unprecedented view of the distinction between the logic of person/hypostasis vs. that of nature/essence: “the hypostasis does not simply or even primarily signify that which is complete, but that which exists for itself, and secondly that which is complete; while the nature signifies what never exists for itself, but most properly that which is formally complete.”6 Nature names the form, which is universal or “common” to all particulars, while person names not only what is particular (“distinguishing characteristics”) but also what alone is concrete in itself. This follows from a hallmark Neo-Chalcedonian thesis, one John the Grammarian first proposed in his Defense of Chalcedon: No nature really exists as such. Rather, natures exist always and only in persons/hypostases. Persons are thus not reducible to natures, although persons only ever act through the formal faculties of the nature they instantiate. In brief: person grounds nature as nature’s real and individual existence, while nature grounds person in another way—namely by empowering the actual individual to act and to be acted upon. From this vantage, any actual existence is an indivisible unity of the concrete person and the nature(s) that person is, i.e. a unity that is existentially one in a truly mysterious manner: here we have an identity that not only allows but even generates difference.

2. Person as synthesis. We see now why Constantinople II introduced “synthesis” to qualify Christ’s person in the hypostatic union of divine and human natures. If person and nature bear fundamentally distinct logics but are inseparable in fact—even and especially in the Trinity—then their actual relations open new ways of conceiving “oneness” and “twoness” in Christ, new conceptions of real identity and difference.

Consider this initially uncontroversial point: Christ’s human nature did not exist prior to its being assumed by the Word, so that the Word’s assumption of his human nature is the very act whereby that human nature exists at all. Neo-Chalcedonians liked to say that Christ’s humanity was enhypostatos or “subsistent in” the Word’s own person, and only there. But this has two immediate and striking consequences. First, it means that Christ’s humanity was not primarily made concrete and individual by anything other than the Word’s very person, since that person in some sense “pre-existed” the humanity and yet was the sole, decisive factor in its being real and concrete at all. Second, it is not just that the Word himself made his humanity come into being. It’s that he himself—in himself—made real the very difference between his own humanity and his own divinity. Thus Maximus says that in Christ we perceive not just the “conjunction” or even “union” of natural extremes (the natures), but in fact “the generation of opposites.”7 Again he says: “Christ himself comprises the interval of the extremes in himself.”8 The way Christ is one—the way he “synthesizes” or “composes” the real oneness of his two natures, is exactly by being an identity that generates natural difference as and through his own self-identity. “By preserving the natures,” writes Maximus, “he himself is preserved, and by conserving them he himself is conserved...if one ceases, the other is completely effaced in confusion.”9

Consider this schema found in both Leontius and Maximus:

And that is precisely what the true account (logos) of the divine economy or Incarnation holds. For through those properties by which his flesh differed from ours—through those very properties he possessed hypostatic identity with the Word. And through those properties by which the Word differed from the Father and Spirit, distinct as Son—through those very properties he preserved intact his hypostatic and absolute oneness with his flesh. No principle (logos) in any way divides him.10

The person of Christ unites three identities at once: [1] natural identity with Father and Spirit (divinity); [2] natural identity with human beings (humanity); [3] hypostatic identity with himself as and in his two natures. Remarkable here is that the Son’s being himself—his identity as begotten of the Father—is simultaneously the principle (logos) of unity and distinction in both the Trinity and the Incarnation. He is God by not being the Father, i.e. by being the Son himself. He is human by the same principle or property—by not being the Father, i.e. by being the Son. It is not divinity alone that makes him who he is, since divinity alone is naturally common to three “who’s,” if you like. Nor is it humanity alone that makes him who he is, since humanity alone is naturally common too. Rather he himself—his personal identity as the Son—is at once the sole principle by which he is united to both his divine and human natures in fact, and also the very principle by which he is who he is relative to the Father and Spirit, and to us. Therefore—and this is the truly astonishing insight—he himself, his very person, is so self-identical that he can really become the principle of the most naturally extreme difference—for what could differ more extremely than created and uncreated natures?—without thereby suffering the slightest division in his own self. His supreme and absolute self-identity as the Son of the Father is exactly the identity posited in and revealed as Jesus Christ.11 “Whoever has seen me,” Jesus says to Philip, “has seen the Father” (Jn 14.9).

Here’s the upshot: Neo-Chalcedonian Christology developed Chalcedon’s distinction between the logic of person and nature exactly to articulate new ways of relating them in the Christ himself. Doing so led to new ways of construing real identity and difference, new conceptions of the “person” as the real “synthesis” of realities that seem (abstractly) impossible to identify with one another. An additional and provocative consequence was that, against the protestations of Severus of Antioch, who wanted to keep the concepts and terms proper to “theology” distinct from the meanings of those same concepts as they are used for the “economy,” Neo-Chalcedonians insisted on the strict univocity of at least one term common to both theology and economy—namely the Son’s very “person.” For surely it is “one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ,” as Chalcedon put it, who exists in the eternal Trinity and in time, who was born of the Father and of Mary, who is consubstantial with Father and Spirit and with us as well. Surely the Son himself is the univocal reality underlying the univocal term linking theology and economy, God and the world, and thus the irreplaceable mediator between God and human beings (1 Tim 2.5).

II. Systematic Promise

A. Twentieth-century reactions. Neo-Chalcedonianism enjoyed an ecumenical yet ambivalent sojourn among twentieth-century systematic theologians. That isn’t too surprising, given that historically it was born of intense debate and inter-ecclesial polemics. Even in the twentieth century many of the scholars who did the most significant historical work on the phenomenon filigreed their work with cautions and criticisms from a certain Thomistic perspective. Charles Moeller, a French Thomist, accused Neo-Chalcedonians of injecting a “monophysite poison” into the otherwise pure marrow of Chalcedon’s schematic, bare-bones definition of Christ. The Neo-Chalcedonian emphasis on identity, which courts the double peril of both dissolving Christ’s human nature below while collapsing the immanent Trinity’s self-identity above, should be duly chastened by the absolute difference between created and uncreated natures. Even sympathizers such as Hans Urs von Balthasar and Sergius Bulgakov, both of whom dedicated considerable attention to notable Neo-Chalcedonians, still bristled at the connotations of the trend toward hypostatic identity in the Christo-logic (though for fairly different reasons and not really consistently). In fact, I know of only a single theologian who explicitly claimed the label for his own style of thinking—the late great American Lutheran theologian, Robert Jenson.

And yet Neo-Chalcedonian Christology has received in recent decades a noticeable ressourcement. In his book, Christ the Heart of Creation, Rowan Williams retrieves Neo-Chalcedonians such as Leontius of Byzantium and Maximus as key complements to Thomas Aquinas and Dietrich Bonhoeffer for a new Christological synthesis. Neo-Chalcedonians feature prominently in Aaron Riches’s Ecce Homo and in Ian McFarland’s The Word Made Flesh. Neo-Chalcedonian ascendency in contemporary Christology is occurring, moreover, even as serious historical scholarship remains fresh (and needed) on major thinkers such as Maximus, who to this day lacks critical editions and English translations of significant works, to say nothing of lesser-known figures such as John the Grammarian and Anastasius of Sinai.

I have argued in print and intend to keep developing the thesis that Neo-Chalcedonian Christology is not just a historical curiosity creeping slowly into the light of day. Its growing appeal is a result of its perennial systematic promise for the very matter of Christology. Specifically, I think that Neo-Chalcedonian “Christo-logic,” as I’ve dubbed it, provides a unique and new vantage from which to re-evaluate and enrich a whole host of central themes, restive controversies, and major thinkers in modern Christology.

That’s a whole research agenda, no doubt. For the remainder of my talk, I will focus on but a single theologian and a single theme in hopes of illustrating the systematic promise of Neo-Chalcedonian Christology: Karl “Rahner’s Rule,” as it’s called, that “the economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity and the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity.”12

B. Rahner’s Rule as Neo-Chalcedonian Christology. The provocative force of Rahner’s Rule lies in the “is” of that axiom. What’s the character of the copula there? What is the sense of affirming the identity of the two trinitarian modes? I suggest that the “is” is principally the consequence of Christological moves of the Neo-Chalcedonian sort.13 Rahner’s Rule, I mean, makes far more systematic sense if seen as motivated by distinctly Neo-Chalcedonian intuitions. That might seem odd because Rahner has relatively little to say about historical Neo-Chalcedonianism, and what he does say betrays a marked ambivalence. But that serves only to reveal Rahner as a still more illuminating case for Neo-Chalcedonianism’s systematic promise: he is only obliquely aware of the specific details of historical Neo-Chalcedonian Christology and yet manages to sense and execute several signature moves that Neo-Chalcedonians once made in a different idiom. Consider just two of those moves.

First, Rahner’s Rule is of a piece with his rejection of what he calls a “mythological” Christology that imagines Christ’s human nature, even logically, as distinct from his very person. “Suppose,” he writes, “we interpret the human nature of the Logos only as something created after a plan or an ‘idea’ which in itself has nothing to do with the Logos.” We might well go on to affirm formally that this humanity was indeed created and should be predicated of the Logos as its agent. But even just conceiving Christ’s human nature as different from Christ empties that nature of any concrete content, so that all we’re imagining here is a blank instance of “universal” humanity, fundamentally extrinsic to the Logos himself. Thus “the human as such would not show us the Logos as such.”14 Instead, the human nature, as really distinct from the Logos, would be reduced to a mere instrument or mask or signal by which the Logos communicated something of himself to us, but not himself. Said otherwise, “the assumed humanity would be an organ of speech substantially united to him who is to be made audible: but it would not be this speech itself.”15 We would witness marvels and wonders, hear sage advice and sound teaching—but none of this is the Son himself. Precisely to the extent that Christ’s humanity functions as the sole or primary mediator of the Word; and if his humanity is never identified with his person in an absolute, irrevocable way—then he himself is not mediator: he has not communicated himself to us.

And so “we must recover that right view of things,” Rahner writes, “which does not (by ‘abstracting’) overlook just that which cannot be really separated from what is human in Jesus: we must learn to see that what is human in Jesus is not something human...and in addition God’s as well.”16

The right view—and this is the second move I wish to consider—is one we’ve already met in the Neo-Chalcedonians: it must be the Logos’s own identity that generates difference. “The unity with the Logos,” says Rahner, “must constitute it in its diversity from him, that is, precisely as a human nature; the unity must itself be the ground of the diversity.” He follows with a nearly exact description of the Neo-Chalcedonian schema we saw earlier, though in quite different terms:

the diverse term as such is the united reality of him who as prior unity (which can thus only be God) is the ground of the diverse term, and therefore, while remaining ‘immutable’ in himself, truly comes to be in what he constitutes as something united with him and diverse from him. In other words, the ground by which the diverse term is constituted and the ground by which the unity with the diverse term is constituted must be as such strictly the same.17

That ground is the Logos himself. Rahner too knows the doctrine of the enhypostatos (though he attributes it to Thomism). He understands it to mean not simply that Christ’s humanity subsists in the Logos but also and more radically that the Logos becomes the concrete “is” of that humanity in such a way that it realizes an absolute self-communication of God as that created humanity: “The humanity is the self-disclosure of the Logos itself, so that when God, expressing himself, exteriorizes himself, that very thing appears which we call the humanity of the Logos.”18

The Logos himself generates not just his humanity but the very difference by which that humanity differs naturally from Christ’s divinity. The Logos himself is simultaneously the principle of identity and distinction. Indeed, his is the personal identity of natural identity and natural difference. No longer is Christ’s flesh a mere instrument. Rather, from the very start, it “is the constitutive, real symbol of the Logos himself”—where “symbol” for Rahner names “an inner moment of” the thing symbolized, which therefore “is itself full of the thing symbolized, being its concrete form and existence.”19 And so what really establishes Rahner’s Rule is another: “here the Logos with God and the Logos with us, the immanent and the economic Logos, are strictly the same.”20

Rahner’s Christology is sometimes reduced to his incidental remark from 1974 that, had he to choose between “an orthodox monophysitism and an orthodox Nestorianism,” he’d choose the latter.21 But this is not because he seeks to indulge a little dualism in order to preserve Christ’s real humanity. It’s rather because he seeks the sort of identity between Christ’s person and flesh that is no “hollow” or “lifeless” or “deathlike” identity.22 He’s after an “authentic sameness.”23 Christ’s authentic identity moves beyond “the purely formal (abstract) schema nature–person” just to the extent that his personal identity means “that here both independence and radical proximity equally reach a unique and qualitatively incommensurable perfection.” Such an identity is for that reason “the perfection between Creator and creature.”24 The Word of God is himself the identity that generates the very difference between God and the world.25 This, then, is the identity that makes God’s economy God’s very self-communication—they can bear the natural differences they inevitably imply (Christ’s flesh, created grace, etc.) exactly because such differences are functions of God’s self-identity as the Three Persons, revealed in Christ.26

Neo-Chalcedonians and Rahner share much, I think. I leave tracking down the details for a later time and more capable minds. I end this comparison by setting together two passages, the first from Rahner, then one from Maximus.

The unity is more original than the distinction, because the symbol is a distinct and yet intrinsic moment of the reality as it manifests itself…. Reality and its appearance in the flesh are forever one in Christianity, inconfused and inseparable. The reality of the divine self-communication creates for itself its immediacy by constituting itself present in the symbol, which does not divide as it mediates but unites immediately, because the true symbol is united with the thing symbolized, since the latter constitutes the former as its own self-realization. This basic structure of all Christianity.27

For in his measureless love for mankind, there was need for Him to be created in human form (without undergoing any change), and to become a type and symbol of Himself, presenting Himself symbolically by means of His own self, and, through the manifestation of Himself, to lead all creation to Himself (though He is hidden and totally beyond all manifestation), and to provide human beings, in a human-loving fashion, with the visible divine actions of His flesh as signs of His invisible infinity.28

I’ve used Rahner’s Rule as one example of how a proper retrieval of Neo-Chalcedonian Christology might illuminate various figures and themes in contemporary Christology. But Neo-Chalcedonianism, since it involved rethinking the very Christo-logic by which both theology and economy might be better grasped, opens a vista from which we might reconceive very many systematic issues, whether perennial or newly contemporary. What might a Neo-Chalcedonian perspective offer to the intractable nature-grace debates in Catholic theology? What can it offer to sacramental theology? What might it say about the way we conceive the relation of the Incarnation to time? And could the latter shed new light upon the relation between the Fall and human origins as currently understood by the evolutionary sciences? Does God’s divine immutability prevent his suffering in all creation and in the victims of human history—a rather urgent concern across twentieth-century liberation Christologies? How did Neo-Chalcedonian Christology permit Maximus to say back in the seventh century, for instance, that God is “always suffering mystically through goodness in proportion to each person’s suffering”?29 Or—to bring it back full circle—could it really be that Adam, “who is we ourselves,” said Ratzinger, is united to Christ’s person such that the Easter message discloses that our very being is grounded in the Word’s own identity, which, as an “authentic identity,” posits us in all our difference? Surely too much ground to traverse. And yet even a little progress on this path seems promising indeed.

Epiphanius, Hom.; PG 43, 440–64.

Joseph Ratzinger, Behold the Pierced One, p. 124. The pronouncement is Ps-Epiphanius’s text, which also quotes Eph 5.14, “Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead….” We can arise from the dead because the Dead One has arisen from the dead, and He is us.

Cyril, Ep. 45.6 (McEnerney 193). Cf. Marcel Richard, Le néochalcédonisme,” Mélanges de sciences religieuses 3 (1946): 160, and Grillmeier, Christ in Christian Tradition, II/2, 434 (who tries to apply this only to “extreme neo-Chalcedonians”).

Esp. now Johannes Zachhuber, The Rise of Christian Theology and the End of Ancient Metaphysics.

Basil, Ep. 214; cf. Leontius of Byzantium, CNE, Test. 1.

Leontius of Byzantium, Epil. 8 (Daley 308–9).

Maximus, Amb 5.14: τῇ τῶν ἐναντίων γενέσει.

Maximus, Ep 15, PG 91, 556A: ἵνα ᾗ καθ’ ὑπόστασιν μεσίτης τοῖς ἐξ ὧν συνετέθη μέρεσι· τὴν τῶν ἄκρων ἐν αὐτῷ συνάπτων διάστασιν.

Maximus, Opusc 8, PG 91, 97A: τῷ γὰρ φυλάττειν φυλάττεται, καὶ τῷ συντηρεῖν συντηρεῖται...ἐπεὶ ταύτης παυσαμένης, παύεται πάντως κἀκείνη, τῇ συγχύσει τελείως ἀφανισθεῖσα.

Ep 15, PG 91, 560AB; my translation.

Maximus, Opusc 8 (op. cit.): The Son himself “made the union and distinction of the extremes [οἷς τὴν πρὸς τὰ ἄκρα ἐποιεῖτο ἕνωσιν καὶ διάκρισιν].”

Rahner, The Trinity, 22.

Be on the lookout for the forthcoming work of Jack Louis Pappas, which will, I suspect, induce a comprehensive reassessment of Rahner’s theology (in method and content alike), sounding notes resonant with yet far more sonorous than those played here.

Rahner, The Trinity, 31–2.

Rahner, “The Theology of the Symbol,” 238.

Rahner, “Current Problems in Christology,” 191.

Rahner, “Current Problems in Christology,” 181.

Rahner, “The Theology of the Symbol,” 238–9.

Rahner, The Trinity, 32; “The Theology of the Symbol,” 251.

Rahner, The Trinity, 33.

Rahner, Karl Rahner in Dialogue: Conversations and Interviews, 1965–1982, 126–7; see Aaron Riches, Ecce Homo, 9–11.

Rahner, “The Theology of the Symbol,” 226–8; The Trinity, 33 n.30, 92, 103, passim.

Rahner, The Trinity, 33 n.30.

Rahner, “Current Problems in Christology,” 162–3.

Rahner, “Current Problems in Christology,” 165 n.26: “[1 Cor 15.28] must be understood in an essentially Christological sense, not as something abstractly metaphysical, ‘permanently valid’; because God in Christ became the world, and so ‘All’ in all.”

Rahner, The Trinity, 101.

Rahner, “The Theology of the Symbol,” 252.

Maximus, Amb 10.77, PG 91, 1165D.

Maximus, Myst. 24, PG 91, 713AB; CCSG 69, 68–9.

Thank you for this. I was reminded of this post when I heard someone talking about the depiction of Jesus in iconography. What side, do you think would a Neo-Chacedonian take on the question of “some children see Him lily white…” (the Christmas song) in which it seems the universal aspect of Christ’s humanity is emphasized over his particularity as an historical first century Jew?

As I read: “A love song: My heart overflows with a pleasing theme; I address my verses to the king; my tongue is like the pen of a ready scribe. You, [Jesus], are the most handsome of the sons of men; grace is poured upon your lips; therefore God has blessed you forever. Gird your sword on your thigh, O mighty one, in your splendor and majesty!” (Ps45:1-3)

Thanks for sharing brother, this is the perfect resource to share with those dipping their toes into this ancient stream. It’s comprehensive and concise at once.