Desert Life

Severe, austere, cold, hard, barren, stolid, and arid—these have very often characterized for me both the setting and spirituality of the desert fathers and mothers. They seem untouchable. They abandoned common life and so became themselves uncommon, exceptional, unrelatable, unapproachable. A spiritual superhero I am not. And, to be frank, the Sayings of these ancient desert dwellers sometimes give just that impression.

Once a very great hermit had a disciple who did something wrong and the hermit said to him: Go and drop dead! Instantly the disciple fell down dead and the hermit, overcome with terror, prayed to the Lord, saying: Lord Jesus Christ, I beg You to bring my disciple back to life and from now on I will be careful what I say. Then right away the disciple was restored to life.

A spiritual superhero unaware of his own super strength! How could I ever relate to him? Or for that matter, to any of these invincible fathers and mothers? Are they not as far from me as they were from the civilized world, bunkered in spiritual warzones fit only for the pious elite?

Lent sometimes strikes me the same way: a spiritual desert for the spiritual elite. Ashes across the brow, death on the mind. And my sins, sorrow, remorse, failure, repentance, penance. This is right and just. Still I wonder: might we return anew to the desert’s ancient inhabitants and seek “a word of salvation,” as they used to say? Might we who now dwell in our own liturgical desert, the Lenten season, see something more than the stark austerity of unkempt terrain and the frail bodies who there keep sleepless vigil? What treasures can we possibly find in this parched plot of our great and wise tradition?

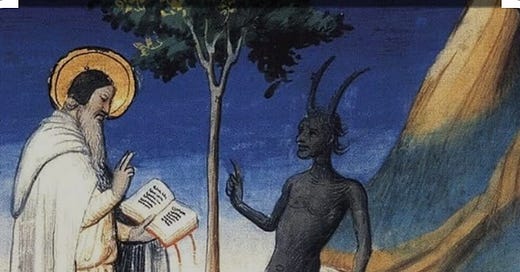

First, a little background. Why did so many men and women forsake city and domestic life for the desert? Many did. Beginning in the third and fourth centuries, so-called “desert cities” popped up around Upper Egypt, Palestine, and Arabia. Monasteries swelled with folks from all classes and backgrounds. What did they seek? What was their purpose? They sought something, and scripture itself seemed to recommend the desert way. It’s the first place Moses led the people of Israel after their great Exodus. Forty years. Many prophets, not least Elijah and Elisha, chose the wilderness precisely because it placed them at the perimeter, as it were, of political power: it provided the requisite distance from which God’s rebuke might sound forth, calling the people away from their many efforts at building Babel yet again. There too, of course, John the Baptist prepared the way for God Incarnate, the Messiah, Son of God, Jesus. Jesus was himself “cast out” into the desert, as Mark’s Gospel says in the first chapter, where, before he did anything else, he fought demons. Jesus often retreated into unknown wildness recesses (thrice in Mark 1 alone). And the first thing the apostle Paul did after his confrontation with the Risen Lord on that road to Damascus was to flee into the Arabian desert, where for three years—well, we don’t really know what he did. (If you go to Petra, Jordan, they’ll tell you he retreated there).

The desert fathers followed these biblical examples. But again, what for? In one sense it was simple escape. Flight from distraction, drama, politics, riches, status—whatever could lull them into a life of spiritual complacency. The conveniences and seductions of city life stifled the soul like water does fire; only in the desert might holy passion burn bright. Theirs was a time when Christianity had just recently become the dominant factor in Roman culture: the emperor Constantine converted, massive Churches erected, ecumenical Councils convened, all with newfound political support and protection. Not long before, some devout Christians might face martyrdom, might have to follow Christ’s pattern to the point of bloodshed. Now no longer. How then to burn for God? How display the truest devotion? Flee to the desert, assume strict discipline—fast, pray, give all your possessions to the poor, do manual labor—and in this way practice “white martyrdom,” as some called it. No blood, but much sacrifice indeed.

There was yet a pious battle to fight, there in the wild where demons slinked about. Those within earshot used to hear St. Anthony’s screams in the thick of night as he warred with evil spirits. On one occasion St. Macarius settled his travel troupe among pagan tombs for a night’s rest. He made a pillow of a mummified corpse, only to be stirred by a malign spirit dwelling within it. Then—and I’m simply relaying what’s recorded!—he began punching the corpse, uttering prayers until the demons fell dumb and left the band to their slumber. In some ways the desert promised the very acts of spiritual heroism that, I’ve admitted, leave me cold.

But none of this was ever the main thing for the desert fathers. The battle they took up was never simply one against demons. It was at bottom a struggle against themselves. Of course the two battles—against demons and against ourselves—could never really be disentangled. Demons only add bricks to the immaterial illusion we have long since constructed of ourselves. They flitter phantoms before our eyes in order to avert our attention from Christ, in whom “our life is hidden,” as Paul says (Col 3.1–2). Such phantoms are more readily confronted in the desert, where the very simplicity of the natural setting encourages the great battle over our vices, which are but delusions of who and what we are. That is already a great insight from the desert: every vice or sin comes from self-deception. Your anger, for instance, comes from a wrong estimation of yourself and what you think you “deserve.” Your lust too. How could you belittle me? Do you know who I am? Shouldn’t I get that? Gotta get what’s mine. But what, after all, is ours, really?

Many fled to the desert, then, not to run away from their problems or sins but to confront them entirely and directly, no distractions. To recall a Lenten theme: they went to repent.

One story recounts how two elders shared the same cell for decades and never quarreled. One elder suggests they try to quarrel “like the rest of men.” So they put a brick between them and one says, “That’s mine.” The other replied, “No, it’s mine.” “Well then,” returns the first, “If it’s yours, then take it!” And so, the saying concludes, these two were so far from anger they couldn’t even feign a little fracas.

A simple way of life is a powerful weapon against self-delusion. Discard as many glittering things as you can and face nothing but your naked soul. There your sin dwells. Yet deeper still awaits the God who alone makes you, you. In his Lives of the fourth-century Egyptian hermits, Paphnutius the Ascetic portrays the whole endeavor of desert living as a delicate alignment of interior and exterior solitude in search for God:

Drawn deeper into the desert, they are drawn deeper into solitude, deeper into themselves and at the same time deeper into community and deeper into God the ground of being, and thus closer to the ground of being within us, for the depth of being in each of us is as strange and alien, yet hauntingly as familiar, as the desert solitude.

Thomas Merton is right, I think, when he sees the whole wisdom of the desert summed up in three words. God spoke these words to Abbot Arsenius while he still lived in the King’s palace, before he went to the desert: “Arsenius,” said the voice, “flee, be silent, rest in prayer—for these are the roots of not sinning.” Flee, be silent, rest. In Latin: fuge, tace, quiesce.

The rest of this Lenten meditation considers briefly each of these. Perhaps they can offer that fresh insight which isn’t always so obvious in a first glance at the desert. Though, I must confess straight out, the first two seem only to cloud matters more. In fact, they look like polar opposites, a patent contradiction.

Fuge (Discipline)

“Flee,” run away, depart from sin, do not see, do not taste, do not touch. Fuge means all these things to the desert fathers. It means discipline. It means becoming holy, pure, fixing your whole mind and life, every hour of every day and night, upon God alone. And to fix upon God, you must remove sin from your own eyes, speck or log.

“There are two things,” Abbot Pastor once said, “that a monk ought to hate above all, for by hating them he can become free in this world. And a brother asked: What are these things? The elder replied: An easy life and pride [or self-centeredness].” They fled to the desert to flee sin, and fled sin by leading a life of sometimes extreme discipline and obedience. This is how they labored to overcome every sort of vice—anger, lust, greed, pride (these mentioned most frequently).

It was said of Abbot Agatho that for three years he carried a stone in his mouth until he learned to be silent.

Abbot Ammonas said that he had spent fourteen years in Scete praying to God day and night to be delivered from anger. (It doesn’t say if he ever was!)

A monk ran into a party of handmaids of the Lord on a certain journey. Seeing them he left the road and gave them [a lot of space to pass by]. But the Abbess said to him: If you were a perfect monk, you would not even have looked close enough to see that we were women.

Once, a great and rich nobleman brought a bag of gold to a desert monastery. He intended to make a charitable donation to their church. The priest told him none of the monks would accept it. So the nobleman laid the bag at the entrance of the church. And there it lay, most monks never even so much as glancing at it, until the rich man finally had to come remove it. At the priest’s request, he gave it to the poor.

Story after story of spiritual heroism, of great and holy struggle against all manner of temptation. You get the sense that these efforts were meant to make spiritual superheroes. And so sometimes in the sayings monks test each other. It’s as if they want to see if so-and-so has really achieved the spiritual level others claim for him.

One story recounts that two brother monks had a reputation for great humility and patience. “A certain holy man, hearing this, wanted to test them and see if they possessed true and perfect humility.” So he went and was received warmly by them. They didn’t know his motive. He saw that the two brothers kept a small garden whose produce furnished their only food. He seized his stick and “rushed in with all his might and began to destroy every plant in sight” until nearly nothing remained. The brothers remained silent. After evening prayers, they invited him to dinner, offering him the sole bit of food left intact—one cabbage. “Then the elder fell down before them, saying: I give thanks to my God, for I see the Holy Spirit rests in you.”

Quite a test. But why test at all? These and similar sayings certainly illustrate the seriousness of the call to “flee,” fuge. They also give the impression of a spiritual contest with all the sobriety of Olympic training.

An elder saw a certain one laughing and said to him: In the presence of the Lord of heaven and earth we must answer for our whole life; and you can sit there and laugh?

If this were the only or even primary side of the desert tradition, I’m afraid it wouldn’t offer us much. It would be like soliciting everyday, basic fitness advice from professional athletes: marginally instructive yet mostly not for us. But it’s not the only or primary side.

Tace (Mercy)

“Be quiet,” silence, take it easy, don’t worry, everything in stride, and most of all, be merciful. These only begin to capture what tace meant in desert life. Alongside severe discipline and spiritual contest grew an unmistakable tenderness, something like warm-heartedness, that could scarcely ever think to condemn anyone else or justify oneself before others. In this sense, the silence of desert life echoes the silence that fell after Jesus declared to those surrounding the prostitute in John 8, “Whoever has not sinned, cast the first stone.”

If, Abbot Macarius once said, wishing to correct another, you are moved to anger, you gratify your own passion. Do not lose yourself in order to ‘save’ another.

Abbot John used to say: We have thrown down a light burden, which is the correction of our own selves, and we have chosen instead to bear a heavy burden by justifying our own selves and condemning others.

An elder was asked by a certain soldier if God would forgive a sinner. He said to the soldier: Tell me, beloved, if your cloak is torn, will you throw it away? The soldier replied and said: No. I will mend it and put it back on. The elder said to him: If you take care of your cloak, will God not be merciful to His own image?

Another story relays that all the elders of a famous monastery (Scete) once assembled because a brother had committed a grave sin. Abbot Moses didn’t care to come. The priest begged him to.

So he arose and started off. And taking with him a very old basket full of holes, he filled it with sand, and carried it behind him. The elders came out to meet him, and said: What is this, Father? The elder replied: My sins are running out behind me, and I do not see them, and today I come to judge the sins of another! Hearing this, they said nothing to the brother but pardoned him.

Somehow, then, the desert fathers thought it just as important—more important—to be merciful with and indulgent of the sins of others as it was to discipline themselves out of their own sins.

Unrelenting discipline and unconditional mercy—how can we harmonize these two? What great contrast! The same saints who fasted sometimes up to seventy weeks; or who intentionally snubbed famous visitors; or who would physically burn their own flesh with fire to stay lustful thoughts in the presence of a temptress—these very same people seemed to harbor almost no intent to apply the same standard to others, even to those clearly in the wrong. Can we discern a common root of these rather different fruits?

An answer comes, I think, in Merton’s introduction to the desert fathers. There he observes the perhaps surprising fact that St. Anthony—the one who fought fact-to-face with devils in desert caves—“thought the devil had some good in him.” Merton rightly says that this was no empty sentiment. Instead it showed, as Merton says, “that in Anthony’s soul there was not much room left for paranoia.” In other words, St. Anthony (like St. Martin of Tours) refused to judge the devil himself, since Anthony had given himself completely over to the mercy of God; and God alone will judge (Rom. 11-12). We need only rest in His utter goodness.

A certain brother came to Abbot Poemen and said: What ought I to do, Father? I am in great sadness. The elder said to him: Never despise anybody, never condemn anybody, never speak evil of anyone, and the Lord will give you peace.

Quiesce (Rest)

“Rest,” calm down, don’t be so uptight, wait, receive, don’t be grumpy, be joyful—I almost dare to say smile—all this and more fill out our final command, quiesce. There’s a quiet confidence to desert life. For all the rigor, extreme practices, severe discipline, and heavy silence, a velvet thread runs throughout it all and holds it together. A single root anchors and nourishes the surprising and often extravagant variety of fruit borne by this part of our tradition. That thread and that root is divine love.

And that love is above all “patient, kind, not arrogant, does not insist on its own way, bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things,” as Paul wrote. We must realize that the three commands—“flee” (fuge), “be quiet” (tace), “rest” (quiesce)—each of these is necessary as far as it goes. But the last is the greatest; it characterizes the whole. Discipline never opposes mercy, nor mercy rest. The desert fathers don’t hesitate to reveal which is better. Love, kindness, and patience with others: these always prevail.

Abbot Hyperichius said: It is better to eat meat and drink wine than to devour the flesh of your brother by complaining about him.

Such graciousness and patience extends even to ourselves. We are to treat ourselves kindly, even in the midst of great discipline and fasting.

An elder said: The reason why we do not get anywhere is that we do not know our limits, and we are not patient in carrying on the work we have begun.

In other words, do what you can within limits—just do something.

Once Abbot Anthony was conversing with some brethren, and a hunter who was after game in the wilderness came upon them. He saw Abbot Anthony and the brothers enjoying themselves, and disapproved. Abbot Anthony said: Put an arrow in your bow and shoot it. This he did. Now shoot another, said the elder. And another, and another. The hunter said: If I bend my bow all the time it will break. Abbot Anthony replied: So it is also in the work of God. If we push ourselves beyond measure, the brethren will soon collapse. It is right, then, from time to time, to relax their efforts.

Fuge, tace, quiesce—“flee, be quiet, rest.” These three flow from a deep trust in the goodness of God, in His infinite love. Very often the fathers say that if we fail to show mercy to others, we are basically claiming that we do not need God as Judge. If we think ourselves too weak to practice discipline, then in this way too we refuse God’s help and power. And if—to state perhaps the most needful insight from the desert—we find ourselves agitated and anxious, never joyful and generally afraid, we have ceased to trust that God is a good Father.

That was in a sense the original sin. When Satan tempted Eve with fruit and the promise that “you will be like God,” he was actually right about the promise. God Himself had said we were made in His image, made to be like Him (Gen. 1.26). The means were wrong. We do not become like God by grasping, seizing, justifying. Christ showed us the true way: He did not consider equality with God something “to be grasped,” and so, clothed in human frailty like ours, he showed us what it means to be like God.

At the same time He showed us God Himself: “He who has seen me has seen the Father.” And it is this above all, I suggest, that the desert has to teach us this Lent: Christ reveals to us a God who can be trusted, a God whose greatest surprise is always the unimaginable excess of His mercy and grace and goodness and love. Knowing this God as our Father, we might truly and finally “rest.” We can stop grasping at grace as if God’s got a tight grip on it. He doesn’t. Because we know He is good, we know He never ceases to give what we need to fulfill each of the commands—fuge, tace, quiesce. The grace of God is like refreshing rain; if you reach up to grab it, you only succeed in shielding yourself from it. Just let it fall.

***

Earlier we were a bit stunned to find an elder rebuking a monk for laughing. Now at length we happen upon this:

The story is told that one of the elders lay dying in Scete, and the brethren surrounded his bed, dressed him in the shroud, and began to weep. But he opened his eyes and laughed. He laughed another, and then a third time. When the brethren saw this, they asked him, saying: Tell us, Father, why you are laughing while we weep? He said to them: I laughed the first time because you fear death. I laughed the second time because you are not ready for death. And the third time I laughed because from my labor I go to my rest.

From ashes to ashes, yes. But for us who know the Risen Lord even in ashes there’s something to smirk about. Nothing is impossible for God. So then, fuge, tace, quiesce, “flee, be quiet, rest.” But don’t forget the one thing needful: sheer delight in God’s goodness. To hell with the lie that anything is more deadly serious than the Father’s love.

Thank you for this wonderful Lenten meditation. Meditating on the points you made, I just had a couple thoughts. The first comes from Unseen Warfare (the Eastern Orthodox edit), where the basic rule he essentially sets out for spiritual warfare which leads to theosis and deification, is for me to realize and completely absorb I cannot do what is necessary to fight this fight and to be healed, and secondly, to thus put all my trust in God to do this for me (of course while I'm conducting basic ascetic or practical disciplines and prayer). The author than goes on to say that if I fail to keep the commandments, if I sin, if my spiritual life gets lax, whatever, that for me to despair over this or even to give into sorrow, shows that I have pride in my own abilities rather than trust in God. The pain of a wounded ego is really just God's medicine. The other thought I had was of Gregory of Nyssa in his Life of Moses, where he essentially says, progress is perfection. It is in the act of following God ever beyond ourselves, ever beyond us, that we are perfected. In any given moment perfection is not being a super hero per se, but rather not falling out of the process of following God up the mountain into the the Divine Darkness or Uncreated Light or whatever.

I know I'm babbling here, but one other thing came to mind. It's quite humurous I think actually. A spiritual son of St. Sophrony of Essex came to visit him one day at the Monastery he established in the UK and looking at him, he couldn't help but sit in awe. This is a saint, he thought. He's really a saint! (He'd been known for miracles and clairvoyance, etc...). And St. Sophrony sensing what this man was thinking punched him in the face (I don't think hard) until finally the person thought--this man is definitely not a saint and Sophrony told the man, he's just a man. To think I can do wonders or rather do them on my own or that I am a saint is deadly--we lose grace. But also to think that because I fail, I am beyond aid, is also pride and we lose grace because inevitably, it always comes down to the fact that, I need God and Grace and faith in his power for I can't do it myself, only he can.

nice reflection, truly.

thanks.

john behr would have us remember though, that while it's been 1700 years since then,

the same Holy Spirit who accomplished all this in all them,

is at the door,

should

you

brother,

but knock.

love has grown cold in the world, 'tis true. but set your sights on heavenly things alone, and you too might become as all flame.

together with you in repentance and prayer this lent;

-mark basil